|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The text face used here (as well as elsewhere) is Broadsheet™. The home page letters are set in Emily Austin™ & Lamar Pen™. All typefaces referenced on this website— Abigail Adams™, American Scribe™, Antiquarian™, Antiquarian Scribe™, Attic Antique™, Austin Pen™, Bonhomme Richard™, Bonsai™, Botanical Scribe™, Broadsheet™, Castine™, Douglass Pen™, Emily Austin™, Geographica™, Geographica Hand™, Geographica Script™, Houston Pen™, Lamar Pen™, Military Scribe™, Old Man Eloquent™, Remsen Script™, Schooner Script™, Terra Ignota™ & Texas Hero™ (as well as all other fonts in the Handwritten History™ Bundle)—are the intellectual property of Three Islands Press (copyright ©1994–2015). For site licensing contact: Three Islands Press P.O. Box 1092 Rockport ME 04856 USA (207) 596-6768 info@oldfonts.com |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Posts Tagged ‘old handwriting’

Sunday, June 5th, 2016

Old Dutch and Malabar scripts. I have in my possession a book published in Amsterdam in 1672. Its author is Philippus Baldaeus, a Dutch Calvinist missionary, and my copy is written predominantly in German. It’s a big book, whose title (translated into English) is A True detailed description of the famous East Indian Coasts of Malabar and Coromandel, and the island of Ceylon.

Baldaeus accompanied Dutch invaders to southern India and Sri Lanka and came back with a tale to tell. This volume—which my father (Germanic languages professor and literary translator A. Leslie Willson) used in researching a book of his own*—has a number of magnificent plates and a series of pages showing samples of the glyphs and letterforms then used in the ancient written language of the residents of Malabar.

Egyptian hieroglyphs (the British Museum). The scripts are truly beautiful—both the exotic Brahmic glyphs of Malabar and the looping Dutch script that accompanies it. And they serve as just one example of handwriting as art.

The earliest writers of course used pictographs, then hieroglyphs (pictures representing sounds), which could certainly be considered art. As might the illuminated manuscripts created by Medieval scribes—but that’s not what I mean. I mean handwritten symbols, Latin and otherwise, whose shapes or execution or both represent art in a fundamental way.

Zapfino specimen. By its very definition, calligraphy is a fine example. The pleasing, expressive sweeps of a calligrapher’s brush or pen can be admired for long moments, can conjure up moods or memories or magic. Calligraphy spans multiple language systems and cultures. In fact, some of the most popular fonts these days are essentially digitized calligraphy—from Zapfino, by late master type designer Hermann Zapf, to the work of contemporary lettering artist Laura Worthington.

Sign painters, poster designers, and graffiti artists also qualify—their hand-rendered letters and words are an unquestionably sincere form of accessible artistic expression. (I’ve received some wonderfully illustrated envelopes from such folks, which I have displayed prominently here and there.)

Detail from Mirabeau B. Lamar’s journal. But leave it to me to carry the handwriting-as-art concept into an even broader realm: the shared experience of people who have written (and, in declining numbers, still write) routinely by hand. Those who have unique or fancy signatures, or who add special little extra loops or curls or flourishes to their regular script (or printing), or who take secret pride in the shapes of their Ps and Qs.

I have a strong appreciation for this kind of handwriting artist’s work. I know it when I see it. I’ve seen it amid the source materials for the pen fonts I’ve made of the scripts of historical Texans—the sweep of the D of Mirabeau Lamar (Lamar Pen), the little vertical cross Emily Austin Perry added to her H (Emily Austin), Sam Houston’s inimitable signature (Houston Pen). Another such font I’ve got cookin’ in the oven adds an interesting twist: the script in Stephen F. Austin’s prison diary, originally written in pencil, was later traced in ink by his nephew, Moses Austin Bryan (Emily’s son).

Detail from Stephen F. Austin’s prison diary. You’ve seen it, too, in the handwriting of certain friends or relatives. Perhaps they heard early on how neat their cursive was, so they took pains to make it more evocative. Perhaps they’re visual artists by nature, and it also carries over onto their notepads. Even sloppy scribblers have quirks curious and endearing. Witness the little crosses on the Zs of Viktorie.

Without question hand-done lettering communicates far more than mere words and sentences—e.g., the mind, age, mood, or proclivities of the writer. Perhaps, in this sort of innate expressiveness, all handwriting might stand as a form of art.

Note: If you know of an example of some particularly artistic penmanship, I’d love it if you’d comment with a link.

*A Mythical Image: The Ideal of India in German Romanticism (Duke University Press, 1964).

Miscellanea

» Award-winning penmanship doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with hands.

» And while were on the subject, here’s another young handwriting champion. Can there be hope for penmanship?

» Perhaps not, as some are editorializing against cursive requirement in schools.

» Meanwhile, archaeologists have uncovered 2,000-year-old handwritten documents in the London mud.

Tags: 18th century handwriting, antique penmanship, calligraphy, cursive script, embellished scripts, Emily Austin font, handwriting as art, hieroglyphs, Houston Pen font, illuminated manuscripts, Lamar Pen font, Leslie willson, neat handwriting messy handwriting, old Dutch script, old handwriting, old Malabar script, petroglyphs, Philippus Baldaeus, pictographs, Texas history, Viktorie font

Posted in Cursive, Graphology, History, Old Letters, Paleography, Penmanship, Ruminations, Specimens | No Comments »

Monday, May 2nd, 2016

I am remiss for not having posted an entry here in so long. The fact of my finally finishing up the first true serif text-type family I’ve ever made is no good excuse (unlike, perhaps, my propensity to enter The Type Design Zone and not emerge for weeks at a time). Anyway, apologies.

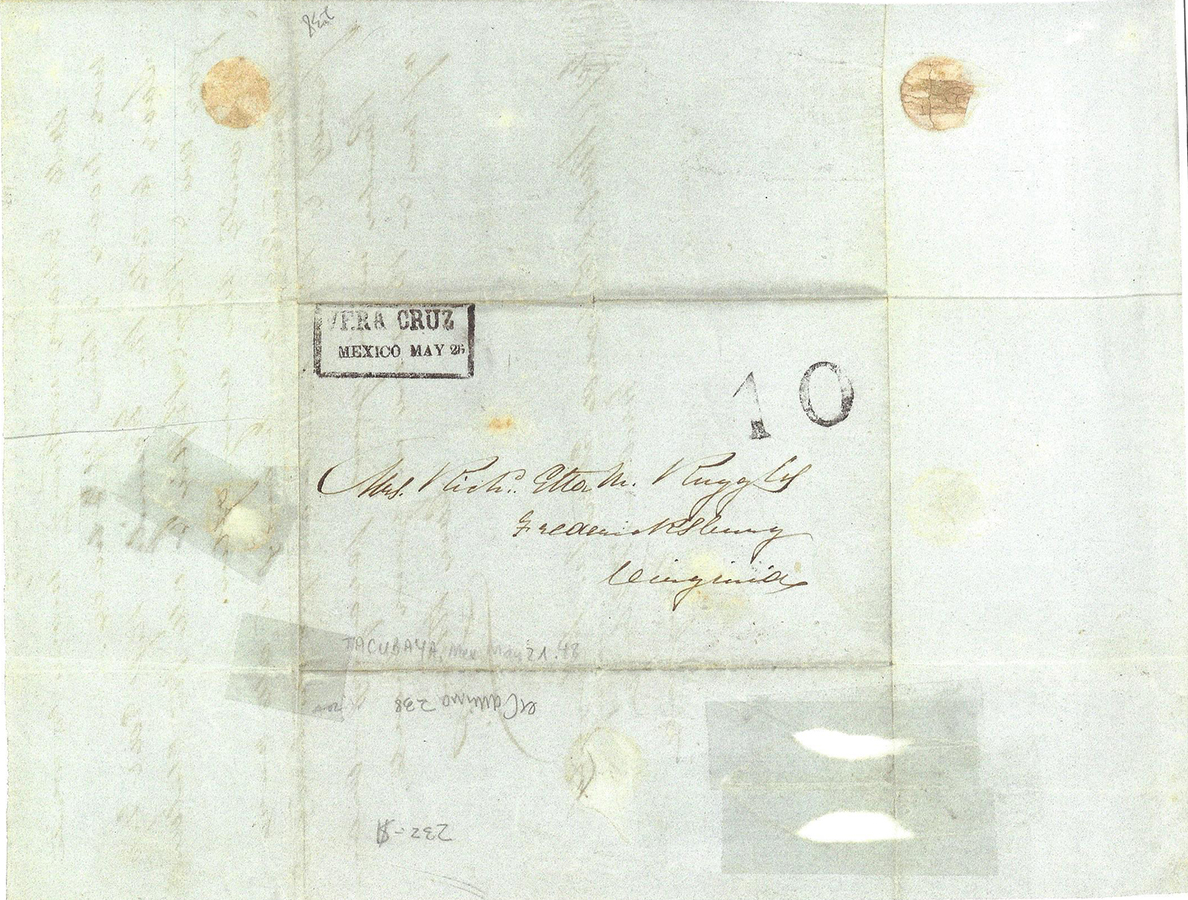

But I have something to share today that I hope will make up for the delay: a dive deep into the quirks and peculiarities of 19th-century penmanship—or at least one man’s peculiar, quirky penmanship—that should give you an idea of how to go about deciphering old handwriting. Or at least how I do it.

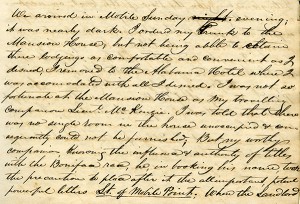

Address page of the Ruggles letter. The penmanship in question appears in a digital scan of a three-page letter (see below) sent to me by an acquaintance who has an enviable collection of historical records and documents from the days of the Republic of Texas. I’d transcribed a handwritten narrative for him already, one whose puzzles were mostly problematic words and short phrases. But this new letter—despite its bold and graceful pen strokes—caught me off guard for its first-blush illegibility. I’ve had plenty of trouble deciphering old handwriting, but at first glance I can usually get a fairly good idea of who had written a thing, or what was being written about. The scan of this letter, with its alluring greenish tinge, seemed more or less inscrutable.

Eventually, though, I managed to puzzle out every word. Here’s how.

An important clue was the destination address on the outside of the folded letter. I’d already looked at the first page, at the date and salutation, but all I could quickly read in the author’s sweeping script was a date that looked like “May 21st, 1838,” the country of origin, “Mexico,” and a town that might’ve been Guadalupe. The outside address was stamped VERA CRUZ MEXICO and had an old notation in pencil that offered two quick corrections: 1) the date was in fact 1848, and the town was Tacubaya (a far cry from Guadalupe!). Upon close inspection, the address appeared to be:

Mrs. Richd Ella M. Ruggles

Fredericksburg, Virginia

Another puzzle. Was this a woman named Ella who was married to a man named Richard Ruggles? At least by now I had determined that the writer’s lowercase “a” looked like an “o” followed by an extra “i”-like stroke. And that the “d” had a very short ascender. After staring for a while I noticed a seemingly random horizontal stroke that told me her name likely wasn’t Ella after all—but Etta.

Daniel Ruggles. I took a peek at the last page of the letter, which the author had stylishly signed with the just his initials, “D.R.” So if this was a husband in Mexico writing a wife back in Virginia, his given name was clearly not Richard.

I pored for a while over the salutation, which—now that I could identify a few odd-shaped letters—I managed finally to work out: “My dearest Etta.” (I was now confident that was her name, from the way the cross of the “t” in “dearest” nearly missed the letter altogether, as did the cross of the double-“t” in Etta.) I soon also had the first paragraph deciphered. Not that it held a lot of clues. Further on I could read a few words and phrases, among them “prospect of peace,” “treaty,” “the 19th inst. Friday,” and what appeared to be the phrase “Chamber of Deputies.” I saw that the author made peculiar “r”s that had a sort of extra squiggle at the end, figured out that those tiny, two-line shapes were ampersands, grew accustomed to his open, unusual “I”s—and realized he was likely in Mexico because of war.

It was time to poke around online.

By searching for “Mexico,” “war,” and “1848,” I confirmed that the Mexican-American War ended in that year. A treaty was signed in February, but U.S. troops didn’t entirely evacuate until August. So I searched for “Ruggles” and “Mexican-American War”—and first on the list of results was a Wikipedia entry for Daniel Ruggles (1810–1897), a Brigadier General for the Confederacy in the American Civil War. I learned that, before that war, U.S. Lt. Col. Ruggles had served in the Texas Campaign, and later, after a long life, had died in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

A search for “Daniel Ruggles” and “Richard Etta” got me genealogical records showing that Richard Etta (or “Richardetta”) was in fact the wife of Daniel Ruggles. I learned that Etta’s maiden name was Hooe, that her middle initial stood for Mason, that she and Daniel were married in Michigan in 1841, and that she died in 1904. I even got a look at the the Ruggleses’ headstone in Virginia.

Armed with this additional background info (which helped also with the seemingly incongruous mention of “Saut on Ste Marie”) and a sense of context, I set to work transcribing Daniel Ruggles’s letter home to his wife, Richardetta. It took nearly two hours, but I got it done.

Deciphering old penmanship can be a puzzle, for sure, but a puzzle that—thanks, ironically, to the digital technology that might ultimately doom handwriting altogether—often promises a circuitous journey through interesting times gone by.

Below are the scans of the three pages of Ruggles’s letter, each followed by my transcription of that page. (Click any page image for a larger view.) I hope and expect you’ll find its contents surprising and fascinating.

The Ruggles Letter, page 1. Tacubaya, Mexico

May 21st 1848

My Dearest Etta,

I have an opportunity to send you a line tomorrow morning early and write you, although I sent day before yesterday one with most things of importance noted.

Today however I can confirm in some measure this report in relation to the prospects of peace & it is therefore I write so soon again— as I am well aware that you are looking for every peaceful sound or show of hope as well as myself.

We have a well authenticated rumour that the Chamber of Deputies confirmed the Treaty 54 in favor to 32 against on the 19th inst. Friday last & sent it to the Senate at 8 o.c. p.m. on that day—this comes from Genl. Butler & is believable.

There is no doubt about the favorable actions of the Senate—and if our information is correct peace is certain.

The Ruggles Letter, page 2. Every preparation has been made for the marching of our Troops towards the coast.

I shall write you now almost daily as I have means of sending letters.

There is some excitement here about a tragic affair of robbery and murder for which Lieut. B. P. Tilden of the 2d Infantry and two volunteer officers from Pennsylvania. Lieuts. Hare & Dutton, have been sentenced to be hanged on the 25th inst. This is the same Lieut. Tilden we saw at the Saut on Ste Marie.

It is said that another officer of the 2d Infy is suspected as an accomplice. The details will soon be published & ring throughout the Union like a bolt of thunder.

Here in the midst of great events these trials have not excited so much interest as was anticipated.

The particulars are voluminous & I must therefore refer you to News as they will appear in the papers. All feel sad for Tildens poor wife, & friends.

The Ruggles Letter, page 3. Well I have nothing more to write nor have I time if I had.

Love to all the Family—kiſs Ed & Tip for me & Roy & Beſsie & all the children do write me very often.

Particular remembrances to all our friends & kind remembrances to the Servants.

Remember me in your prayers—dream of me & kiſs me in your heart.

Ever thine

D.R.

To/ Mrs. Richard Etta M. Ruggles

Fredericksburg

Virginia

[Note on the last page Riggins’s use of the old-style long-s (“ſ”) in the words “kiss” and “Bessie.”]

Miscellanea

» Turns out 400-year-old handwriting is even trickier to read—and can result in surprises.

» Speaking of transcriptions, Norfolk County, Mass., has digitized 250,000 old deeds—including a few historic ones.

» For its 500th anniversary, The Royal Mail is urging UK residents to dig out old handwritten correspondence.

» Going back way farther: handwriting from 600 B.C. suggests widespread literacy—and an older Old Testament.

» And although it might be delaying the inevitable—the teaching of cursive penmanship ain’t dead just yet.

Tags: 1800s, 1848, 19th century, antique handwriting, antique penmanship, cursive script, Daniel Ruggles, deciphering old handwriting, historical letters, letters home, Mexican-American War, old handwriting, old letters, Texas history, transcribing old handwriting, vintage handwriting

Posted in Cursive, Historical Figures, History, Old Letters, Paleography, Penmanship, Uncategorized | No Comments »

Tuesday, March 8th, 2016

The Palmer Method of cursive script. I have my hand, and I have my pen. That’s it. —Rev. Robert Palladino

A few days ago I listened to a fascinating Freakonomics Radio podcast called Who Needs Handwriting? In exploring the question of its title, the episode features an interview with Anne Trubek (@atrubek on Twitter), a writer, editor, and former professor who knows a lot about writing by hand. Trubek, who is author of the forthcoming The History and Uncertain Future of Handwriting, essentially argues that kids don’t need to learn penmanship anymore.

It all started, Trubek says, when her son began having problems in second grade—strictly because of his poor handwriting skills. So she wrote an article for Good magazine with the bold and declarative title Stop Teaching Handwriting. It drew a lot of interest.

The Gregg Method of shorthand. And she has a point: young people of today might well go far in our technology-driven world without so much as ever touching a pen. What use is it for us to continue to embrace what was originally a strictly utilitarian skill out of some romantic sense of self, a part of our individuality?

Then again, the Freakonomics podcast goes on to tell us, research shows that students who take notes by hand recall a lot more of a lecture than those who merely transcribe what’s said via keyboard. So should we perhaps be reviving shorthand (a skill my father practiced, much to my childhood incredulity and awe)? Not so much, turns out—it’s a lot closer to straight keyboarding.

Still and all, cursive script appears to be on the way out—other than as a fine art form. Fewer people over time will be able to read engrossed old documents. Who among us these days, after all, can interpret the early hand-scribblings of, say, a Sumerian skilled at cuneiform?

Rev Robert J Palladino (at Reed College). On the other end of the handwriting spectrum, you have a celebrated scribe like Rev. Robert J. Palladino, who died a couple weeks ago. Palladino was a Trappist monk when he began learning the skills that made him a master calligrapher who, at Reed College, influenced Apple co-founder Steve Jobs’s design of the Macintosh computer. Jobs credited a Palladino calligraphy course he audited with helping inspire the whole idea of digital typography.

“[The Mac] was the first computer with beautiful typography. If I had never dropped in on that single course in college, the Mac would have never had multiple typefaces or proportionally spaced fonts.”

In a delicious twist of irony, of course, a master with a pen helped further our mass migration over to the keyboard. But there’s something to be said for Father Palladino’s own unwired life—replete with its long periods of thoughtful silence—and his having never once used a computer in 83 years.

[Hang on, time to check Facebook—brb.]

In keeping with my overarching theme here (i.e., handwriting as a sense of self), I’d like now to share another old handwritten document I’ve used as source material for a font I’ve designed. Below are page scans and a transcription of a two-and-a-half-page letter written 18 September 1825 by Samuel Clarke, then pastor of the Congregational Church of Princeton, Massachusetts, seeking donations for the victims of an accident at sea. Inspired by Clarke’s extremely distinctive penmanship, I designed Schooner Script back in 1996. [Note: the boat was in fact a sloop, but Sloop was a script already.]

The Schooner Script letter, page 1. Princeton Sep. 18. 1825

Christian Brethren,

It is known probably to most of you, that several of our acquaintance and friends, in coming from the State of Maine to this Town, have been exposed to the most imminent danger, and also sustained a considerable loss of property. As their danger and misfortunes have excited much sympathy; and as it is believed to be a Christian duty to do something for their relief, it may be proper, for the correct information of all, to make a short statement of the peril to which they were exposed, and the extent of their loss.

On Saturday the 10. inst, at 12.o.clock, Messrs How, Fay and Cobb with the wives of the two last, and eight other persons, sailed from Camden for Boston in the Sloop Governor. Their passage was favourable until about 8.o.clock on Saturday evening, when the Sloop was struck by another vessel which was apparently in distress, and whose fate is not known. The Sloop was so much injured by the unknown vessel, that she very soon filled with water, which, communicating with lime in the hold, caused her to take fire. Being unable, by the greatest exertion, to save the Sloop, the Captain with his men and passengers was obliged to abandon her, and consign themselves to a small Boat only thirteen feet long and about five wide. our friends were compelled so hastily to leave the Sloop, that they had no time to secure their trunks and clothing—and had they been even able to do this, the smallness of the Boat to which they fled, would not have admitted any additional weight. In this small Boat thirteen feet long, thirteen persons

The Schooner Script letter, page 2. passed the whole of Saturday night on a boisterous, dangerous sea, some of them destitute of outer garments, and all of them in constant danger of immediate death. It is impossible for us to know, much more to describe their anxiety, their anguish. But a benevolent and merciful Providence watched over, and preserved them, when death appeared inevitable. After having been in this dangerous, distressing situation nine hours, they were discovered on the morn of the Sabbath by another Sloop which immediately came to their relief, and rescued them from impending destruction. In this Sloop they arrived in Boston on Tuesday morning, and on Wednesday were permitted to rejoice in again beholding this their native Town, and receiving the kind welcome and sincere sympathy of their acquaintance and friends.

They desire, with unfeigned gratitude, publicly to acknowledge the goodness and mercy of God which watched over and saved them in the season of extreme peril, which preserved them from the watery element, and which has again restored them to the arms of their brethren and friends—

It may be proper to state that Messrs How and Fay saved their money, with the exception of a small sum lost by Mrs. Fay—but they lost a considerable amount of property in clothing. Our young friends Mr. and Mrs. Cobb lost nearly five hundred dollars, about four hundred of which was in money, and the rest in new and valuable clothing.

There can be no doubt, Brethren, respecting our duty in relation to the misfortune of our friends. While we sympathize with them, we should also assist them in bearing the burdens which a wise Providence has seen fit to lay upon them. It has been suggested by several respectable persons that the easiest and most effectual method of rendering them assistance, would be to request a contribution in each of the religious Societies in this Town on the

The Schooner Script letter, page 3. next Sabbath. In accordance with this suggestion a contribution will be requested in this place in the afternoon of the next Sabbath, when it is hoped that our charity will correspond with our ability and the necessities of our friends, and manifest for us that we do truly sympathize with them in their sufferings, rejoice in their preservation, and are anxious for their future comfort and happiness—

Samuel Clarke

Pastor of the Congregational Church

in Princeton—

Miscellanea

» Lamentations continue over the decline of cursive—from pen companies, forensic scientists, and autograph collectors.

» Does playing with old-fashioned toys help kids learn better handwriting skills?

» Handwriting analysts go to town on a note left by a guy who found a wallet full of stuff—but didn’t return it all.

» It might be fading generally, but certain local school districts continue to find time for handwriting instruction.

» A thoughtful essay by Dolly Merritt about what penmanship used to mean.

Tags: Anne Trubek, calligraphy, common core, engrossed documents, Freakonomics podcast, Gregg shorthand, handwriting in schools, old handwriting, old handwriting fonts, penmanship as expression, Robert J Palladino, Schooner Script, sense of self, Steve Jobs, the palmer method, vintage penmanship

Posted in Cursive, Education, Graphology, Historical Figures, History, News, Old Letters, Penmanship, Science, Specimens, Uncategorized | No Comments »

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|